No Lemons in Baseball Cards

The year was 1969.

At the time, it sounded like a good idea. We were going to make our own baseball cards. These were going to be no ordinary cards, mind you. They were going to be the best cards ever. While other kids were wasting their time selling lemonade from front-yard stands, our sweet-looking baseball cards were going to be the hit of the neighborhood.

To a couple of 11-year-olds, it seemed like a relatively simple proposition.

We had already successfully staged our own garage production of Batman, complete with bat costumes, bat sets and bat music and paying bat audience. Making baseball cards… what was the big deal? Heck, an astronaut was going to walk on the moon. Making baseball cards would be easy.

Well, things didn’t go exactly like we had planned.

Maybe we shouldn’t have tried to cut corners by using cardboard from clothing boxes. Maybe we shouldn’t have insisted on using Old English lettering in tribute to our World Champion Detroit Tigers. Maybe our carefully drawn pictures of our favorite players weren’t so hot. What did they want? Norman Rockwell? Maybe it was a mistake not to type all those stupid stats on the back.

I really don’t know. All I know is that we didn’t get rich quick. We didn’t even get rich slowly. But what did we expect? We never even got to packaging, let alone marketing our cards. Gum? Nobody really cared about gum; let them buy lemonade from Johnny down the street.

Then we got to thinking. Maybe there was money in lemonade after all.

There is no exact science when it comes to making baseball cards. Certainly, there are specific stages of production that are intrinsic to the process. But the practice of making baseball cards – and judging from the early efforts of some card manufacturers, it does take practice – is basically an art form.

Now, nobody is ever going to compare a baseball card to a Picasso or a Van Gogh, but a person could reasonably argue that a baseball card is a miniature reproduction of art. Whether or not you like a certain card – like any work of art – is largely subjective. Not every collector may have liked the paint splashes on the 1990 Donruss cards, but there’s no denying the influence of artist Jackson Pollock (“Jack the Dripper”) on the design.

Of course, if Rembrandt or Renoir were still alive, it’s hard to imagine them designing baseball cards. Taking spray cans to subway trains might have been more their speed. But they might – even though there’s nothing romantic about the creation of a baseball card.

It falls to marketing people like Neil Lewis, director of baseball services for Donruss, to prick people’s bubbles about the mystery of baseball card manufacturing.

“People figure that somewhere there’s a guy in a beret with a big palette of paint, designing baseball cards,” Lewis said. “Or they picture a bunch of old men with cigars, huddled in a smoke-filled room. But it’s not that way at all.”

The reality is that a baseball cards is simply a product, the end result of a long list of production and printing steps. But baseball card romantics, take heart. It all starts with a dream.

“Our philosophy starts with the idea to make the perfect cards,” said Julie Haddon, public relations director for Score, which arrived on the baseball card scene in the late-1980s.

Ask any group of 11-year-olds about their idea of the perfect baseball card and you’ll likely get more different answers than there are card companies. And that’s a whole lot.

Sharp action photos? Nice portraits? Attractive borders? Team logos? Player signatures? A simple design? Full-color photos on the back? Full career statistics? Lengthy player biographies? Bubblegum that doesn’t taste like it was chewed yesterday? It all fits into the mix. Certain things are simply more important to some card companies.

Designing, creating, and producing millions of perfect baseball cards is no easy task. Come to think of it, designing, creating, and producing even bad baseball cards is no easy task. Some companies just make it look easier than others.

“I truly believe that all the card companies are trying to do what they perceive is best,” said Don Bodow, director of marketing for Upper Deck. “I think every company takes a lot of pride in their product.”

Still, there are a lot of myths that surround the making of baseball cards. Some of them were even true once. But not any more.

MYTH #1: Anybody can make baseball cards.

Long before a company can even begin to think about making the perfect card, it needs licenses. A driver’s license or hunting license just won’t do. A company that wants to make baseball cards has to apply to the Major League Baseball Player Association for a license that will allow the company the right to use the player’s photos on its cards, and to Major League Baseball Properties for a license to use team logos and other regulated trademarks.

Obtaining these licenses is no simple order. Anyone wishing to make baseball cards better be prepared to forfeit their first-born child, scadloads of money and the right to recoup their investment for several years. They also had better be prepared to offer up reasons on why they want to make cards, why their product is different or better than all the other card products, and how this product will benefit mankind. And the reasons better be good.

Once a company has its license application approved – typically after months of assorted delays – it has to pay royalties to both the MLBPA and MLB. The royalties consist of millions of dollars, up front. A card company is out big bucks before it even makes its first card.

The actual process of making a baseball card begins at the design stage. Here a card company can show its true colors – indigo, turquoise, olive or gold in the case of Donruss, teal and fuchsia for Score, plain white if it’s Upper Deck. The choices are countless. Some companies just like making choices more than others.

MYTH #2: Anything short of plaid could become a Donruss border design.

At Donruss, a team of graphic designers and management personnel get together to discuss the possibilities. Several mockups are presented, and the choice usually comes down to one design.

“It’s pretty tough to put your arms around and explain,” said Lewis about the process. “Each year it means injecting something a little different. There are various sources of stimuli for our designs. Our people look at what’s in vogue in art, in fashion, in printing techniques. We’re sensitive to what kids are buying in merchandise and clothing.”

In fact, a multitude of design decisions confront an art department, including graphic styles, choice of colors, type size, and whether to include player positions, team logos or facsimile autographs. “It’s a tedious process to finalize,” said Score’s Haddon. “Usually, there’s a method to the madness,” Lewis adds.

For its 1991 set, Donruss developed 66 slightly different border treatments. Is there a point at which a company can get carried away? Lewis doesn’t think so.

“With being daring, there also comes a risk,” Lewis said. “We can’t please you every year, but we hope that we please you most of the time. To us, it’s a compliment when someone says a design has a Donruss look.”

Donruss began to take a more innovative approach to card design in 1984 after a couple of “dud” years. “Basically, I think we thought about it too much,” Lewis said. “The worst design decision you can make is to take a little bit of this, a little bit of that.

“You never want the design to overpower the intent of the card. A good border should act like a good picture frame – should complement the photo.”

MYTH #3: Once you get the license and come up with the design, the rest is easy.

Nightmares abound among baseball card manufacturers. First-year experiences are often enough to send any sane person into long hibernation.

“Our first year was the worst experience of my life,” Lewis said. Haddon’s experience was similar. “When we got our license, it was just rush, rush, rush,” she said.

In trying to handle the rush, many companies seemingly resort to unusual photography techniques. Donruss used the experimental “Taking Pictures in Near Darkness” technique in 1981. Fleer opted for the “Bleery-Eyed Party All Night” technique in 1982.

“It all starts with the camera and the people behind the camera,” said Upper Deck’s Bodow, who should know. At Upper Deck, top-notch photography is absolutely crucial. Take away its full-length photos and you won’t end up with much more than a tiny foil hologram on high-quality paper.

“Our philosophy is that our cards are creating an image of baseball,” Bodow said. “We want to tell the story of baseball. The more space we can give to the photo, the better. We find that’s important to collectors.”

To insure the best possible photos – whether front or back – each company’s photo department sorts through thousands of slides. From the final selections, black-and-white copies are made. These matched prints are cropped to show only the rectangular image that will appear on the card, then matched to a border and an overlay with the player’s name and team logo.

Meanwhile, the slides are “separated” – enlarged to the proper size, then made into negatives for each of the primary colors in the printing process (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black). Color separation is one of the most critical stages in production, and one of the most expensive.

“It’s really the most important stage because your cards are only as good as what you start out with,” said Lewis. “We’re always looking, evaluating. We want to know: Does it look good?”

That look depends partly upon the paper on which the card is printed. Cards sliced out of stock with the quality of a pizza box are going to look rather, uh, cheesy.

Unfortunately, paper can be more temperamental than an overpaid ballplayer. Humidity can play havoc on stocks, and not all paper accepts ink or cuts the same way. “Sometimes paper can have varying characteristics throughout a run,” Lewis said.

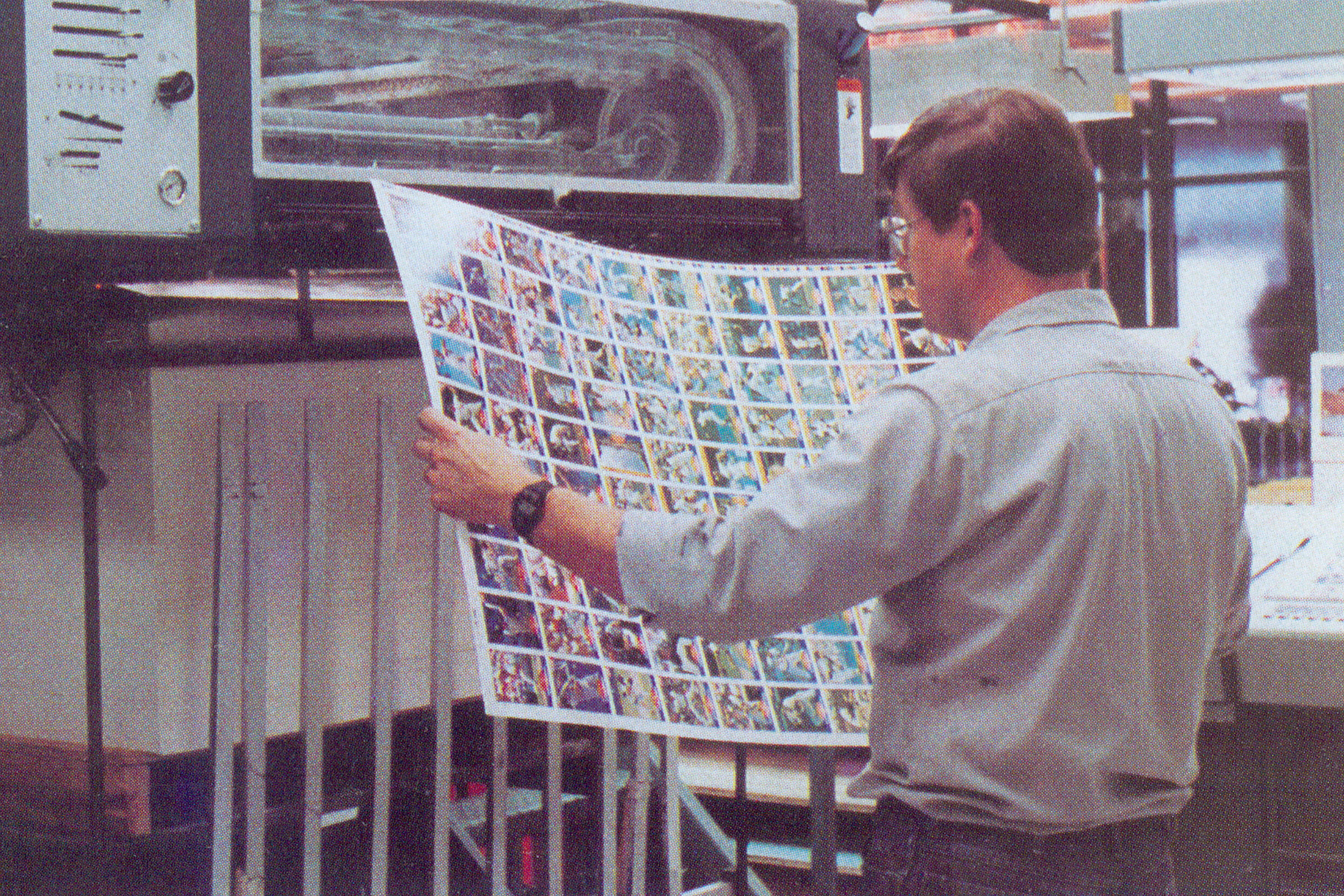

Before the actual printing of the cards begins a high quality proof called a chromalin is produced. Those proofs are mounted onto sheets or forms, from which the offset printing plate is made. The sheets vary in size, determined in part by the number of cards in the set.

MYTH #4: Nobody looks at the backs of baseball cards.

Everybody knows that kids don’t read, right?

While checklists are being checked and pictures picked, information is being collected for the card backs. For whatever reason, most card companies are sketchy about their sources. Topps, for instance, refuses to reveal the name of the Shakespeare who writes those thrill-a-minute one-liners like “Once worked on a construction crew in Minnesota” or “Dave has aspirations of being an accountant.”

The backs of baseball cards have not been a priority for most manufacturers – until recently. Score scored points with collectors when it began printing full-color portraits and lengthy profiles written by former Sports Illustrated editor Les Woodcock. “Remember, we want to create the perfect card, and a card has two sides to it,” said Haddon.

MYTH #5: Upper Deck cards aren’t really paper; they’re made from recycled Wonder Bread.

The clean, white-bread look of Upper Deck is created with a special process that coats both sides of its premium paper.

“We do that for two reasons,” Bodow said. “The first is aesthetics, which is probably not a good word to use around seven-year-olds. Suffice to say, it makes the card look nice. Secondly, it helps the durability of the card.”

Using an ultra-white paper of high quality helps, too.

“We use a paper that is specially formulated for Upper Deck,” Bodow said. “We select a paper that will complement everything we do, just as our inks are specially selected.”

MYTH #6: The number of errors has a direct correlation to the number of cards in a set. Unless, of course, the company wants to boost sales. Then everything goes.

Companies check the chromalins for errors, but any last-minute changes come at a stiff price. “We have to change a whole sheet of film, not just one card,” explained Haddon, who estimates it costs Score $2,000 every time it pulls a sheet.

Companies vary in their attitudes toward errors. Topps will almost never correct an error. Fleer has gone on record this year as saying it will correct no errors. In the past, it has been one of the top error-correctors in the business. Donruss corrects errors somewhat indiscriminately. Upper Deck corrects most photo and design errors. Pro Set corrects anything and everything. Again, it all depends on the company involved.

Complicating error hype and almost everything else this year is Donruss’ and Score’s announcements that they will issue cards in two series. Production will continue on the first series until early spring when the presses will stop and printing of the second series will begin.

“It’s going to take a lot of effort; it’s twice the work,” Lewis said. “There are manufacturing scheduling problems, but we think the ability to update player movements and add special cards highlighting the award winners will make it a dynamite set.”

Upper Deck complicates its production process further by adding a small hologram, a laser-etched foil designed as an anti-counterfeiting measure, to the back of each card. Produced by an outside supplier, the small holograms are carefully applied during production in Upper Deck’s own California printing plant.

With all details complete to this point, card manufacturers start rolling the presses for a short test run to make color corrections. When colors don’t register correctly, you get baseball cards with a 3-D look – only you don’t need the 3-D glasses and you’ll end up with the crossed eyes your mother always warned you about.

“The system’s not perfect, so we have a number of quality checkpoints and try to have a fresh set of eyes checking all the time,” Lewis said. “If you look too long, everything starts to look the same.”

MYTH #7: When you work in a baseball card factory, you get to keep all the cards you want.

Baseball cards, like the players they depict, are dumped when they’re not good. “Cards rejected are totally destroyed and shredded,” Lewis said. Nobody wants mutilated Mattinglys, so workers have to keep a watchful eye on the machines that crank out, cut, collate, and package the cards.

“These machines, developed by a staff of engineers, are designed to produce certain tasks specific to baseball cards,” Lewis said. “Every year, you tweak the process to make it a little better.”

Cutting and collating (sorting cards by number) is all done by machines. “It’s so high-speed, you can’t see the cards, but you know it’s working because the sheets are disappearing,” Lewis said.

Packaging uses a whole gamut of materials, from wax paper, cellophane, and Mylar, to the peek-proof, tamper-resistant foil pack used by Upper Deck. Packaging is the last stage in production, but the first step to a sale.

Making baseball cards involves a lot of the same complicated procedures that were required 20 years ago. Currently, it doesn’t appear like the process will get any easier. But someday, just maybe, it might all get simpler and 11-year-olds will be able to act like baseball kings and have it their way.

Anyone want to see my life-size holographic projection cards?