A Batting Title Doesn’t Always Bring Fame

Winning a batting title is certainly no minor accomplishment.

For a player to lead his league in hitting, he has to make steady contact with the ball day in and day out. Every plate appearance can make a difference in his batting average. An extended slump can knock a guy out of a batting race quicker than a high inside fastball.

But a high batting average calls for more than consistency over the course of a full season. It demands the ability to “hit ‘em where they ain’t.” And it takes extra concentration and determination to perform as the pressures of a batting race mount.

Yet, in spite of the enormous odds that must be overcome to capture a title, many batting champions have become all but forgotten.

Leading batsmen from the distant past – players like Debs Garms, George “Snuffy” Stirnweiss, and Lew Fonseca – are just names from the record book.

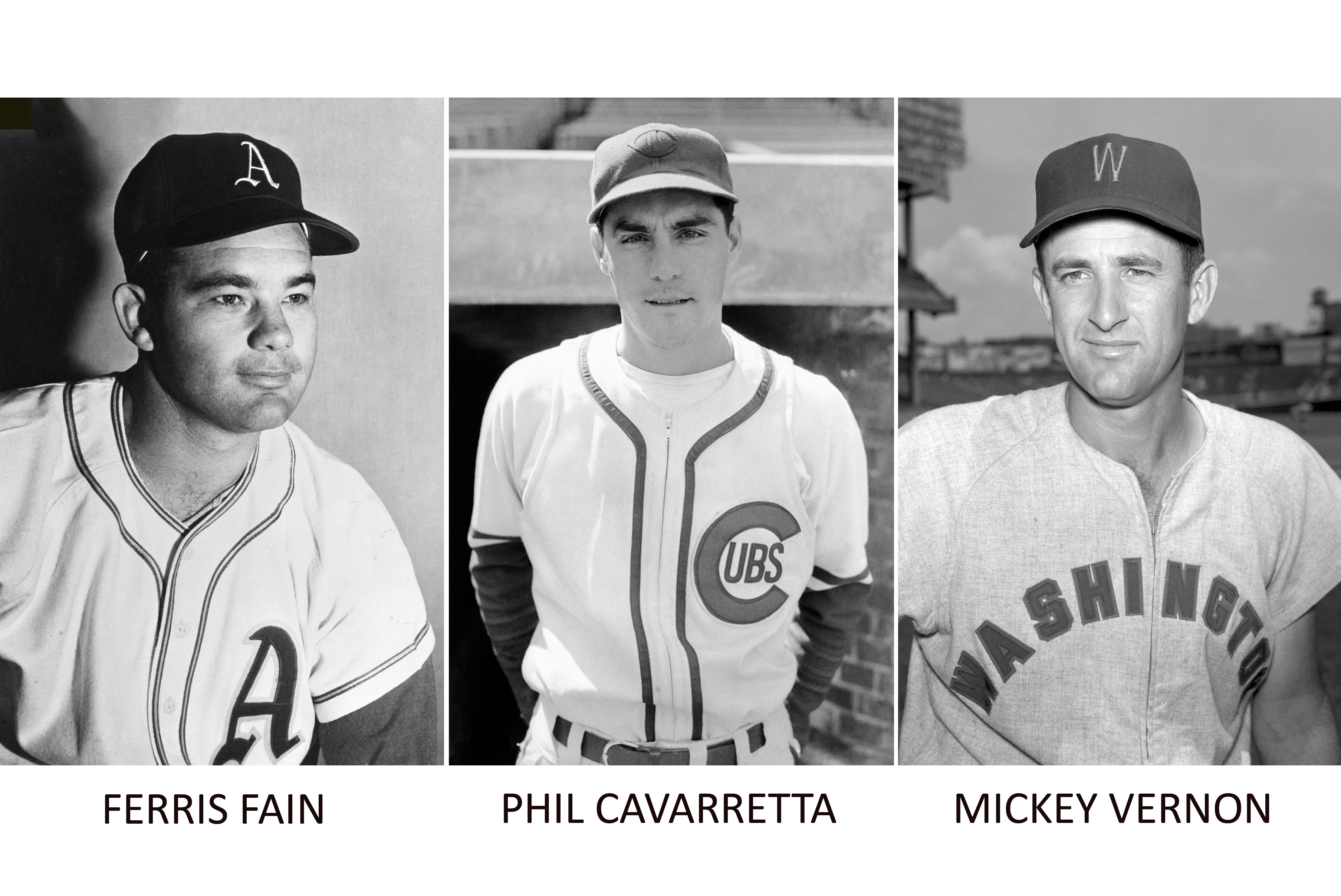

The accomplishments of fine players like Roberto “Bobby” Avila and Phil Cavarretta are not etched in our memories as they should be. Even those fortunate to have been a batting champion twice – such excellent hitters as Ferris Fain, Pete Runnels, and Mickey Vernon – are not given the recognition due them.

Underrated and underappreciated, they became anonymous talents toiling in the shadows of the great sluggers of their era: Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and the rest.

The accolades, the media attention, and the big salaries typically went to the guys who could muscle the ball over the fence. The guys with the batting titles just got to keep the memories.

“In a way, I think it’s something I appreciate more today,” said Fain, who won back-to-back batting titles in 1951-52 while playing for the old Philadelphia Athletics. “Now when I realize that I beat out guys like Mr. Williams and Mr. DiMaggio, I puff up a bit. But at the time, it was just a nice feeling.”

Like many of the “forgotten” batting champs, Fain was a contact hitter who believed getting on base was more important than slugging the ball out of the park – an attitude that helped win games but didn’t attract headlines.

“I’m one of those people who hold the opinion that the home run is horribly overrated,” said Fain, whose career high was 10 round-trippers.

Still, many fans would rather see a player slam a home run in the clutch than watch a little guy finesse a couple of base hits off a tough pitcher. Consequently, the fat contracts go to the power hitters. Singles hitters – even if they win batting titles – get short shrift.

“It was true back when I played and, I think, is still true today,” said Vernon, who managed to hit 172 homers during his 20-year career.

A hitter who used the whole field, Vernon was a victim of the park in which he played most of his career. Washington’s Griffith Stadium was 405 feet down the left field line and 420 feet to dead center. The dimensions help explain why he hit 117 of home runs on the road.

“I probably would have hit more at home, but the ballpark had a high fence in right field. So I hit a lot of doubles instead,” said Vernon, who led the American League in two-baggers three times.

But immortality is not earned with frequent singles, walks, or even doubles and triples.

Few people, for instance, could tell you that Fain was consistently among the league leaders in base-on-balls and that he topped 90 free passes in seven of his nine big league seasons. In fact, Fain had a lifetime on-base average of .425, one of the all-time best percentages.

“I had a good eye,” Fain explained. “I’d work the pitcher to a 2-0 or 3-1 count and then look for my pitch. I was not going to chase a bad ball.”

While Fain may have had an excellent hitting philosophy, it was not one that would win him the Most Valuable Player award.

Generally speaking, sluggers with eye-popping home run and RBI totals take home the MVP trophy. Sometimes, a league’s top hitter gets barely noticed.

Take, for example, Garms, the National League batting champ in 1940 while playing in 103 games for Pittsburgh. That year Garms finished tied for 13th place in the MVP balloting by the Baseball Writers’ Association.

Certainly, there have been exceptions, although when batting champs have taken MVP honors, they have almost always played for first place teams.

Pete Rose took the award in 1973 when he hit .338 to lead the Cincinnati Reds to the N.L. West title. Shortstop Dick Groat, sparkplug of the 1960 World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates, batted .325 to win his league’s top honors. An MVP performance from Cavarretta led the 1945 Chicago Cubs into the World Series. As his team’s field captain, Cavarretta hit .355 to win the batting crown.

“It was a thrill, but more important to me was the team winning the pennant and getting into the World Series,” said Cavarretta, who twice batted over .400 in the autumn classic. “The Series is the goal of every big league ballplayer and yet so many good players have never made it.”

Some critics might downplay Cavarretta’s 1945 showing due to the fact that his best year came at the close of World War II when many players were still away in military service.

“I’m not too proud to admit it,” Cavarretta said. “Sure it was a war year, but there were still a lot of good ballplayers around.”

In his defense, Cavarretta batted .294 the following year when all the players had returned and he hit .314 in 1947.

On the other hand, it is apparent the major league’s supply of talent dwindled during the years 1942-45, making way for players of lesser skills.

Stirnweiss became the 1945 A.L. batting king by hitting .309 with 10 home runs for the Yankees, then batted .247 with 10 homers over the next six seasons.

The players who finished second and third in the American League batting race in 1945 fared even worse. Tony Cuccinello and Johnny Dickshot of the Chicago White Sox were released after the season even though they had hit .308 and .302, respectively.

Some batting champions find their talents overlooked because their best years happen alongside other great players. The previously mentioned Runnels and Billy Goodman won batting titles with the Boston Red Sox while Ted Williams was still the toast of the east coast.

Not many fans outside of Cleveland may remember Avila, whose American League-leading .341 average in 1954 was somewhat lost in the record-setting exploits of his team. The Indians claimed 111 wins that year, with Avila, Larry Doby and Al Rosen, plus pitchers Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, and Bob Feller.

Conversely, there have been batting champions who have toiled in the obscurity offered by playing for losing or last place teams.

Vernon played for the old Washington Senators, a team that struggled to post only two winning seasons during his 14 years with the club.

“I never felt overlooked,” Vernon said. “There were eight teams in the league then and Washington was one of them.”

Still, Vernon admitted that he might have fared better, at least financially, had he played someplace else, like in New York.

“I probably didn’t make as much money as if I had been laying for the Yankees,” Vernon said without a hint of remorse. “Washington didn’t draw too many people, so they just didn’t have the resources. It was pretty tough to get raises in those days.”

Vernon won his first batting title in 1946 when he hit .353 to finish ahead of Ted Williams and his .347 average.

“It was a big thrill,” Vernon remembered, “because everybody was coming out of the service and it meant beating out Ted Williams, the greatest hitter I ever saw.”

Vernon’s second batting title came seven years later when he hit .337, edging out unanimous MVP Al Rosen, who hit .336 with 43 homers and 145 RBI.

“I cost him the triple crown,” Vernon says with a tinge of guilt. “Al and I were very good friends.”

In between his titles, Vernon had several rollercoaster-like seasons during which his average fluctuated wildly. He hit .265, then .242, following his phenomenal .353 season, then rebounded with a couple of .290 seasons. He hit only .251 the year before his .337 season in 1953.

The inconsistency no doubt tarnished Vernon’s reputation as a fine hitter.

“I sure did go up and down like a yo-yo,” Vernon said. “It’s not the first time I’ve been asked about that. But I don’t have an answer for it.”

Fain, on the other hand, can explain how, at the age of 30, he managed to up his average to .344 in 1951.

“Something funny had to take place for a guy to suddenly go from .280 to .340 after 12 years of professional ball.

“Nobody wore batting gloves back in those days and in spring training that year I developed blisters on both hands. I didn’t want to miss my turn in the batting cage, so I choked up on the bat four or five inches. I just tried to meet the ball and every time I swung, I’d hit a line drive.

“Well, I’m not the dumbest guy in the world, so I switched to that grip and it made all the difference.”

Fain insists that too many players go for the glory and aim for the fences when they should be thinking more about bat control.

“Almost all home run hitters have big strikeout totals and 110 or 120 strikeouts can hurt you more than 30 homers will help,” Fain said. “To me, there’s nothing more final than a strikeout. Give me a guy like Nellie Fox or a George Kell – somebody who can keep the ball in play.

“A good example of what I’m talking about is this kid playing with Texas, Scott Fletcher,” Fain said. “Now there’s a kid who is using his head and just doing what he can. I see him choked up on the bat two or three inches and he’s a lot better hitter now.”

Most batting champs weren’t flashy players because they tend to be disciplined hitters concerned with making contact to drive the ball through a hole in the defense.

A check of post-World War II batting champs shows only two men who topped 100 strikeouts during the season they won their titles: slugger Dave Parker fanned 107 times in 1977 when he hit .338 and Roberto Clemente struck out 103 times when he hit .357 in 1967 (an uncharacteristically high total for Clemente).

Since 1945, batting title winners have struck out an average of only 52 times a season.

Without question, winning a batting crown requires a lot of hard work. And sometimes the dedication pays off handsomely.

“A good example is Don Mattingly of the Yankees,” Cavarretta said. “He’s proof that it takes a lot of concentration and dedication to become a great hitter. You’ve got to be willing to take that extra batting practice.”

That competitive urge has marked the careers of many batting champions. Sometimes the drive to succeed becomes so strong that it can be detrimental to a player’s own good.

Fain remembers such an experience during the year of his first batting title. He had popped out with a man on second base twice in the same game.

“That happened to be against my religion, so I got mad at myself,” Fain recalled with a laugh. “I kicked first base in a fit of anger, broke my foot, and was out six weeks. Needless to say, my manager, Jimmy Dykes, was a little unhappy about it all.”

While that was an unlucky break, Fain felt he had his share of good fortune in becoming a two-time batting title winner.

“There’s a heck of a lot of luck involved in winning a batting title,” he said. “First off, you’ve got to be lucky some guy is not hitting better than you.

“But you know things are going your way when you hit a 14-hopper, seven guys dive at it, and no one comes up with it.”

Some hitters are good enough to make their own breaks.

“In my estimation, Wade Boggs is the finest hitter I have ever seen,” Fain said. “You never see this guy hit a fly ball and with artificial turf, that can add 30 points to your average.”

Players like Boggs, Rod Carew, and Tony Oliva have made winning batting titles look easy. But Fain contends leading the league in hitting year after year is no simple feat.

After hitting .327 in 1952 to win his second batting title, Fain watched his average drop to .256. Traded by the Athletics to the White Sox, he discovered teams began to defense against his punch-and-judy hitting style.

“The first time I batted against my old teammates, left fielder Elmer Valo looked like he was playing shortstop because he was in so shallow,” Fain recalled. “He had been watching me for two years, spraying the ball just past the infield with absolutely no power. From then on, they started getting me out.”

By now, it should be obvious that it takes a special talent to win a batting title. But 20 years from now, will fans remember such previous winners as Carney Lansford, Al Oliver, and Willie Wilson?

It will be interesting to note what people will remember about Tony Gwynn, who rather quietly hit .370 this past season – the highest average in the National League since Stan Musial hit .376 in 1948.

What people should never forget is winning a batting championship is never as easy as it looks.

"When you’re hitting and tearing up the league, the outfield looks like an airport,” Fain said. “When you’re in a rut, it looks like they’re playing with seven outfielders.”